Context and background: governing through insecurity

The state governs and disciplines through insecurity. Welfare reform and public sector cuts associated with austerity comprise part of this discipline, but insecurity can’t be understood fully without also taking into account the hostile environment and the broader casualisation of employment and housing. Casualisation is also related to austerity; for example, the defunding of social housing means that social housing providers increasingly rely on funding through private rents.

These precarities reinforce each other and download the burden of cost onto individuals and families. The following discussion is theoretically grounded in the idea that this cost translates as the heightened labour of social reproduction, in particular the labour of reproducing and nourishing intimate relationships. People have to work harder mentally, materially, and emotionally to establish and maintain bonds, because these relationships are mediated through cumulative precarity.

More broadly, my PhD attempts to integrate social reproduction and reproduction-as-family-creation by focusing on the ways people strive to love and care, and the temporality involved in that striving. My research really confirmed for me that people don’t think about biological reproduction in isolation from other forms of care and dependency. Reproduction does not start with conception and birth. Undoing that idea helps us to decentre genetic paternity and actually recognise the work of marginalised subjects. It also allows us to understand that the uncompensated extraction of this work is the process by which power is constructed – this is basically how I am using queer feminist political economy.

This presentation is based on PhD research conducted in 2017 and 2018 that looked at the ways that young people living in rented accommodation in Hackney form and sustain intimate relationships amidst housing and employment precarity.

Popular discourse around generational obstructions to reproduction have prompted critique regarding a) class analysis and b) the types of reproduction being obstructed; not everyone is sad because they can’t have their ideal hetero nuclear family home. Some people want children on their own. Some people want relationships of care that aren’t centred around children. Some people don’t have a choice.

This is not to say that economic policies over the last eight years haven’t disproportionately affected young people – tripling tuition fees, scrapping EMA, decline in real wages. We just have to take more things into account when considering what reproductive obstruction might mean.

My research tries to do this by exploring the ways that reproductive impingement is thought about and experienced by a cross-section of millennial renters in Hackney.

I spoke to twenty-four people aged between 23 and 36 living in a variety of tenancies across Hackney. With most participants I carried out two interviews, with the second in their own home. I recruited participants through children’s centres, housing groups, unions, and more informal networks I’d built over the years as a teacher, activist and renter in Hackney. Hackney is a good place to look at disparity as well as solidarity because so many people are different from each other but experiencing comparable issues, albeit at different levels of extremity.

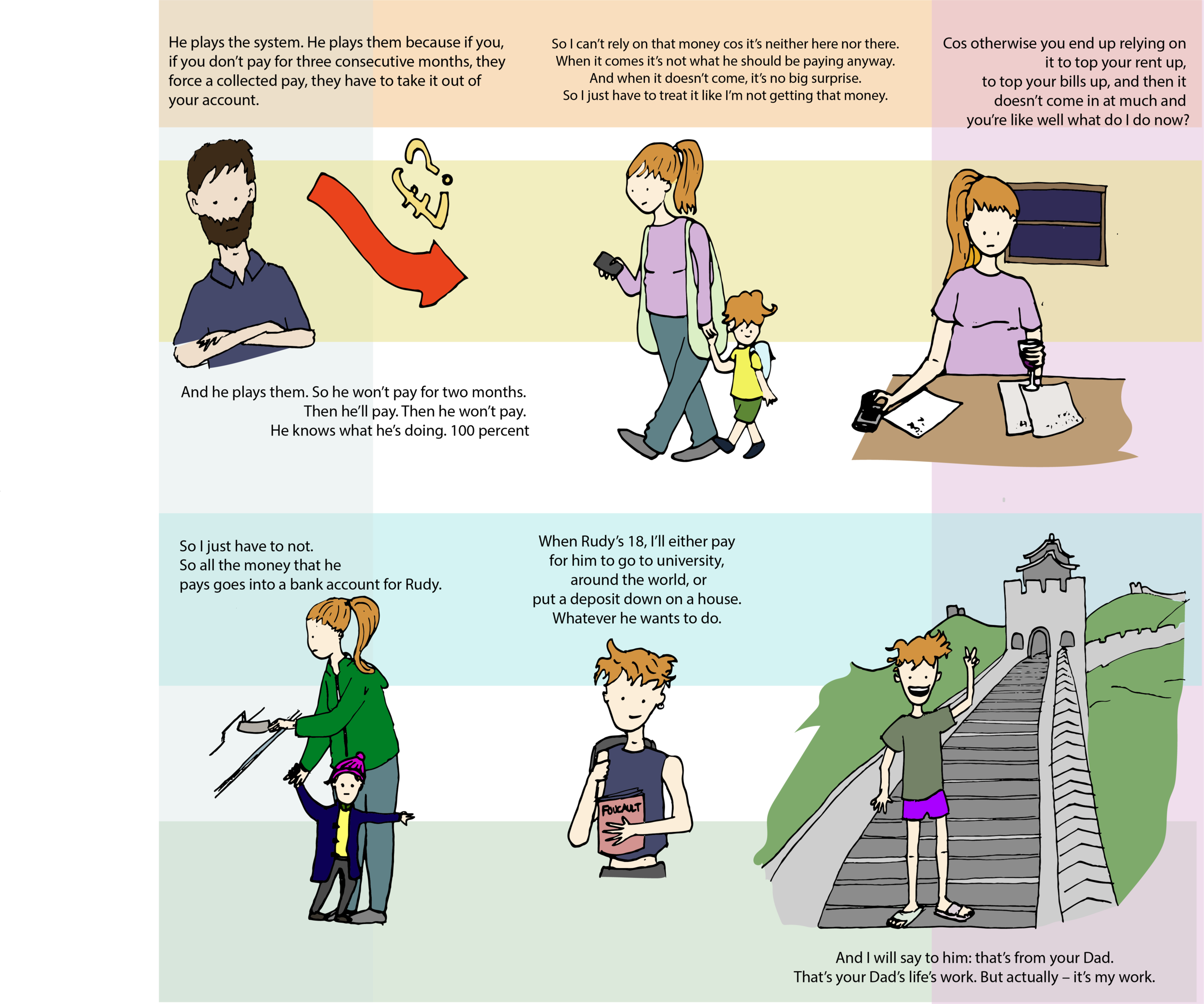

A key part of my analysis and dissemination involved illustration – I’m compiling anonymised comics as a resource for my participants and grassroots groups

Study findings illustrate the malleability of reproduction and kinship in precarious times, the significance of capital in formulating linear reproductive trajectories, and the permeation of economic precarity within experiences of intimate unsafety

This paper is going to look at five empirical examples of cumulative precarity engendering costs to people’s relationships.

Abdul

Abdul was 24 at the time of our discussions and living in a council-rented flat in Dalston with his parents and sister. He is an actor and has sporadic work on screen and stage. He had lost multiple service jobs because of casting calls but refused to give up his professional ambitions despite immense pressure from his parents. His low income and the unaffordability of private renting in his area meant that he was forced to stay at home. However, he was also locked into staying at home because of the unoccupancy penalty, which meant that if he left the house he would be effectively putting his family at risk of eviction.

He described to me that his financial and housing situation had destroyed his relationship with his ex-girlfriend.

Tinashe

Tinashe was 26 when we had our interviews. At the time she was living in a council-rented house in Clapton with her father and two sisters. She has spent some years as a child in foster care with her younger sister and twin. Owing to the way that social services intervened during this time, she was still estranged from her mum. As she was growing up her mum had struggled with her mental health and was evicted repeatedly. Tinashe described how one of the recent social housing accommodations that her mum had been in was effectively a private tenancy with constant changes in residents and serious disrepair. She told me that it was practically impossible to maintain a relationship with her mum because her mum was embarrassed by the conditions and she and her sisters were put off by them too. She also explained that a no-fault eviction notice had meant that she no longer even knew where her mum was.

Jonathan

Jonathan was 29 when we spoke. At the time, he lived in a privately rented one-bedroom flat with his partner, but he told me that he had lived in multiple private tenancies in Hackney over the past five years. Jonathan recalled a time that he and his partner decided to lodge in a friend’s house to escape a particularly dire rental property in Bethnal Green. He explained that the ostensibly supportive and stable environment of living with someone he knew in a house that she owned was initially appealing. However, she quickly put the rent up, sullying their friendship and forcing him and his partner out of the house.

Nouman

I met Nouman when he was 24. At the time he was living with his parents, sister, two brothers, sister-in-law, niece and nephew in a house in Homerton rented from a housing association. Nouman family had come to the UK has refugees in the 90s. His older brother’s wife was not from the UK or EEA and his brother did not currently meet the financial requirements for sponsoring her spousal visa. Housing unaffordability and his brother’s financial situation meant that they had to live in the family home with their two children. The overcrowding caused tension and conflict but also engendered fear of economic and legal penalty. Firstly, Nouman’s sister-in-law does not have the legal right to rent in the UK. There is also complete legal ambiguity as to whether extra lodgers are allowed in homes rented from housing associations. Moreover, any extra money contributed by lodgers to the overall rent is considered income, which can affect housing benefit.

Maja

Maja was 28 at the time of our interviews together. She had been bouncing around different live/work warehouse tenancies in Hackney Wick for the past two years. She told me that her mother had died when she was 22 and had left her some money, which buffered the regular shortfalls she had in income from her zero-hour job at a local bar. She explained that, up until recently, she had been sharing a room with her boyfriend, who had no job and no money. His financial situation had hastened their moving in with each other, and their constant proximity created tension. This tension was often grounded in unwanted dependency, shared space, and conflicting schedules.

Concluding Remarks

Capital obstructs and impinges upon love, attachment, care, and desire

Through welfare reform, hostile immigration policies, and the casualisation of both housing and employment, the government both directly and indirectly intervenes in intimate life

This intervention is partly grounded in demographic ideologies around who gets to make what type of family or network

While the ideological grounding of such interventions is explicitly racist and misogynist, they are channelled through a logic of profit that is presented an inexorable, e.g. the recent doubling of the immigration health surcharge is presented as justifiable owing to the need for NHS funding; social housing provision, also gutted by austerity, is presented as requiring funds from private market rents

It is normal that capital would be the mode through which this engineering is executed, because profit is the financial expression of power. By extracting more money and more work from the poor and marginalised, hegemonies are preserved.

People nonetheless strive to circumvent impingement, to nourish their existing bonds and form new ones. Any concept of reproductive obstruction needs to take this into account.